It occurred to me that some of you reading these essays might wonder why I write so much about what’s wrong with health care. The short answer is because I’m so sure we can do better. The longer answer is more personal.

Writing has always been my way of expressing feelings—joy, sorrow, and everything in between. Some people shout. Others reflect quietly. Some people sing. Still others pray.

I write.

I’ve spent more than 40 years trying to make health care better—sometimes with joyous success, but more often with frustrating failure. The older I get, the more troubled I am by the failures. Getting back into my professional head, two particularly vexing problems with American health care keep me up at night: end of life care and mental health. And the way I think about both has been shaped by experiences along the way.

One of my essays here on Substack addresses end-of-life care, a topic I’ve written about professionally for years. But when I reflect more deeply on the strength of my views, I realize that personal experience plays a role too.

Nearly 25 years ago, my dad died. A suicide.

It still feels awkward to type that word. But too many American families have experienced the sudden loss of a loved one for silence to feel noble. So, I’ll say this: I dealt with it the only way I knew how. I wrote.

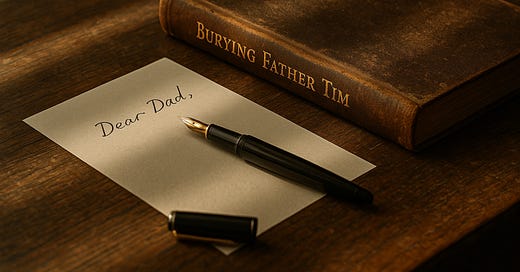

Not essays. A novel.

I grew up Catholic. Went to Catholic school - which, let’s be honest, is a gold mine for humorous stories. But losing a parent the way I did is a mineshaft of grief. The intersection of grief and humor felt like a good place to go - someplace to write my way back to okay.

So I imagined a man my age returning to his childhood hometown for the funeral of his boyhood parish priest. The entire story takes place in a single day, alternating between events at the funeral and flashbacks to his Catholic school upbringing. Some moments are hysterical. Others, deeply poignant. As the day unfolds, the main character wrestles with mortality—and memories.

In the book, his dad dies. Not by suicide. There’s time for goodbye. Time to say things that shouldn’t go unsaid.

Here’s a brief passage from the book:

“Dad, do you remember what you told me the night I got married?”

He may or may not have remembered, but he knew that I was building up to something, so he stayed quiet and waited. I reminded us both of what he said in the twilight that night in Carmel.

“You said that every time we say goodbye, a part of us stays behind.”

He nodded. “That’s right.”

“Well, for as many more days as we have, I’m going to say goodbye every night, because I want you to leave as much of yourself behind as you can.”

My eyes were filled with tears, and my voice cracked. My dad squeezed my hand and looked at me with clear and fearless eyes.

“You’ve got everything you need, Michael.”

He closed his eyes and drifted off to sleep. I sat beside him, watching his chest rise and fall, still holding his hand. The door opened quietly and my mom’s silhouette was outlined in the bright lights of the hallway outside. She and Annie slipped into the room, speaking in whispers. They would stay with my dad for an hour or two, and then head back to our apartment for the night. I was on call, so I would be in the hospital all night. I stood up from the chair, bent down to my father’s ear and whispered, “So long, Dad. I’ll see you in the morning.”

A few pages later:

I turned toward the nurses’ station and reached to adjust my stethoscope, which was hooked around my shoulders as always. I took two steps and turned around, catching Annie just as she was going back into my dad’s room.

“Annie?” I called. She turned, one hand still propping the door open.

“Yes?”

“Make sure they page me if anything happens.” She nodded.

“I’ll remind them before we leave,” she said. Then she blew me a kiss.

My pager went off at 2:37 in the morning. Twice before that night, I had been paged by the emergency room to evaluate trauma patients. I instinctively reached for my pager and pressed the button that illuminated the message window. If it was the emergency room, the message would be flashing. I squeezed the pager and read the message: “Room 3215, STAT.” Room 3215 was my father’s room, and “STAT” means immediately in doctorspeak. I set off at a full sprint for the elevators.

I could hear my heart pounding in my ears as I ran. I pressed the elevator button and bounced up and down on the balls of my feet while I waited for the doors to open.

When I reached the room, there was no commotion. The chief resident was waiting for me, but no one was rushing around; in fact, the only sign that anything was wrong was the bright overhead light. Ordinarily, overhead lights are turned off at night to allow patients to sleep. I looked at my dad, and it looked like he was asleep, but I knew better. I paused just long enough to detect no rhythmic rise or fall of his chest. I looked at the chief resident, who put his hand on my shoulder and said he was very sorry.

I slumped into the bedside chair and reached for my dad’s hand. It was heavy. I laid his arm down gently and leaned forward against the rail of his bed. It took a conscious effort to breathe. I thought I had prepared myself for this moment, but you’re never really ready. After a lifetime of leaving little bits of himself behind, my dad was gone.

When my wife Sandy read that chapter, she hugged me and said, “You finally got to say goodbye.”

I think she was right.

There is something profoundly good about passing gracefully. And something jarringly bad about not. It’s what my earlier essay meant by the term “a good death”. The reverberations of getting end of life care wrong can echo through children and grandchildren. We have a term for it…generational trauma.

With advances in medical technology that have extended and enriched lives, we have inadvertently brought with it disruptive complications to what were natural endings. As a country, we struggle to find the right balance. So when I see our health care system fumble the ball at the end of life—when we miss moments that matter—I get frustrated. I get sad. And I write.

Thanks for reading.

This isn’t a book promotion, so I’m not including a link here. But if you’re curious what I wrote back in 2008, the book is called Burying Father Tim. Sandy tells me it’s a warm and funny read.

But then again, she’s my best friend.

Thanks Rich. The academic medicine community has been my extended family for 30 years…none more than you, old friend.

Tom— You truly have the gift of writing and moving the heart and mind. Thank you for sharing your story and inviting others in.